The Call to Sportsmen – Sport Unites Project

“How very different is your action to that of the men who can still go on with their cricket and football, as if the very existence of the country were not at stake! This is not the time to play games, wholesome as they are in times of piping peace. We are engaged in a life and death struggle.”

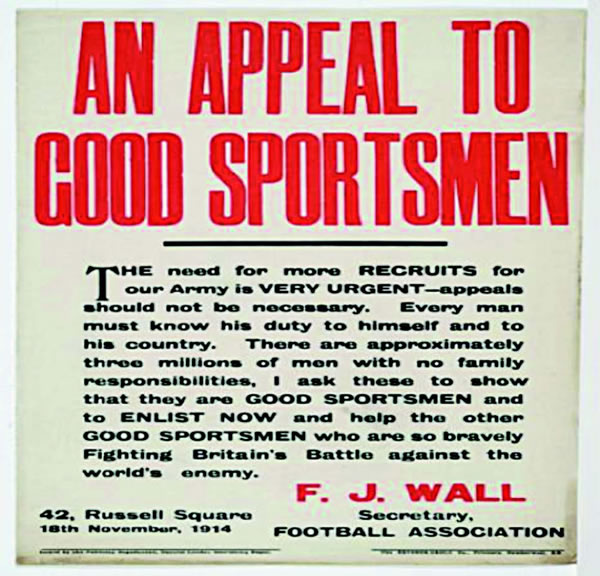

When Field Marshal Lord Roberts spoke these words on 29 August 1914, his message could not have been clearer: it was time for Britain’s sportsmen to stand up and be counted. Britain had declared war that month and Lord Kitchener’s recruitment drive – “Your Country Needs YOU!” – was on its way to enrolling 500,000 men in its first four weeks.

The campaign to enlist sportsmen – notably the footballers and cricketers who appeared to be the most reluctant to enrol – intensified in early September with the public intervention of a leading writer and commentator, Arthur Conan Doyle, the Sherlock Holmes author, an amateur footballer and MCC cricketer in his younger days.

By the end of September, more than 50 towns and cities had established one or more Pals’ Battalions, among them sportsmen’s battalions, and three of those comprised mostly football players, club officials and supporters.

Casualties amongst Sportsmen

It is impossible to quantify the precise number of British sportsmen who made the ultimate sacrifice in the war. Of almost nine million British Empire soldiers mobilised, around one

in eight – or 1.1m individuals – were killed in battle or went missing, presumed dead. Another two million were wounded. On the front line, one in five perished.

Of 5,000 professional footballers at the time, more than 2,000 signed up. Using average mortality statistics, several hundred probably fell in the fields of Europe, with more dying later from their injuries.

Tottenham Hotspur staff enrolled and fought together from 1915, and the deaths of 11 of them were recorded in the club’s handbook after the war. Newcastle United lost seven men, the same number as Hearts, three of whose players – Harry Wattie, Duncan Currie and Ernie Ellis – died on 1 July 1916 alone, on the opening day of the Battle of the Somme.

A team-mate, Paddy Crossan, was so badly injured that his right leg was tagged for amputation. He begged the surgeon: “I need my legs, I’m a footballer.” The leg was saved but Crossan, 22, died later of damage to his lungs from poison gas.

West Ham lost five players, and Orient three, all in the Somme, with others injured so badly their careers were over. At Bradford and Celtic, Preston and Hibernian, Bristol City, Arsenal, Manchester United and all points in between, star players were lost.

Cricket suffered a disproportionate number of deaths (almost one in six who went to war). At least 34 first-class players were killed among 210 county players who served. Kent and England’s Colin Blythe, a left-arm spinner regarded as one of the best of his era, took 100 wickets in 19 Tests. He was killed by random shell-fire on a railway line during the Battle of Passchendaele on 8 November 1917.

Rugby union prided itself as a sport that played its part. By the end of November 1914, every England international from the past year had signed up, while a 1915 war recruitment poster declared: “Rugby union footballers are doing their duty. Over 90 per cent have enlisted. British athletes! Will you follow this glorious example?”

There was an inevitable price to be paid. The England captain, Ronnie Poulton-Palmer, was killed by a sniper’s bullet in 1915 and was among 27 England internationals who died. Thirty Scottish international players lost their lives, and 11 Wales players.